Abstract

Background: Epilepsy is a persistent tendency to experience epileptic seizures and can lead to various neurobiological disorders, with an elevated risk of premature mortality. This study evaluates the efficacy of brivaracetam adjuvant therapy in patients with epilepsy.

Methods: A prospective observational multicentre study that was conducted in Pakistan from March to September 2022, by using a non-probability convenience sampling technique. The population consisted of 543 individuals with a diagnosis of epilepsy for whom adjunctive brivaracetam (Brivera; manufactured by Helix Pharma Pvt Ltd., Sindh, Pakistan) was recommended by the treating physician. The research sample was drawn from various private neurology clinics of Karachi, Lahore, Rawalpindi, Islamabad and Peshawar. Data originating from routine patient visits, and assessments at three study time points, were recorded in the study case report form.

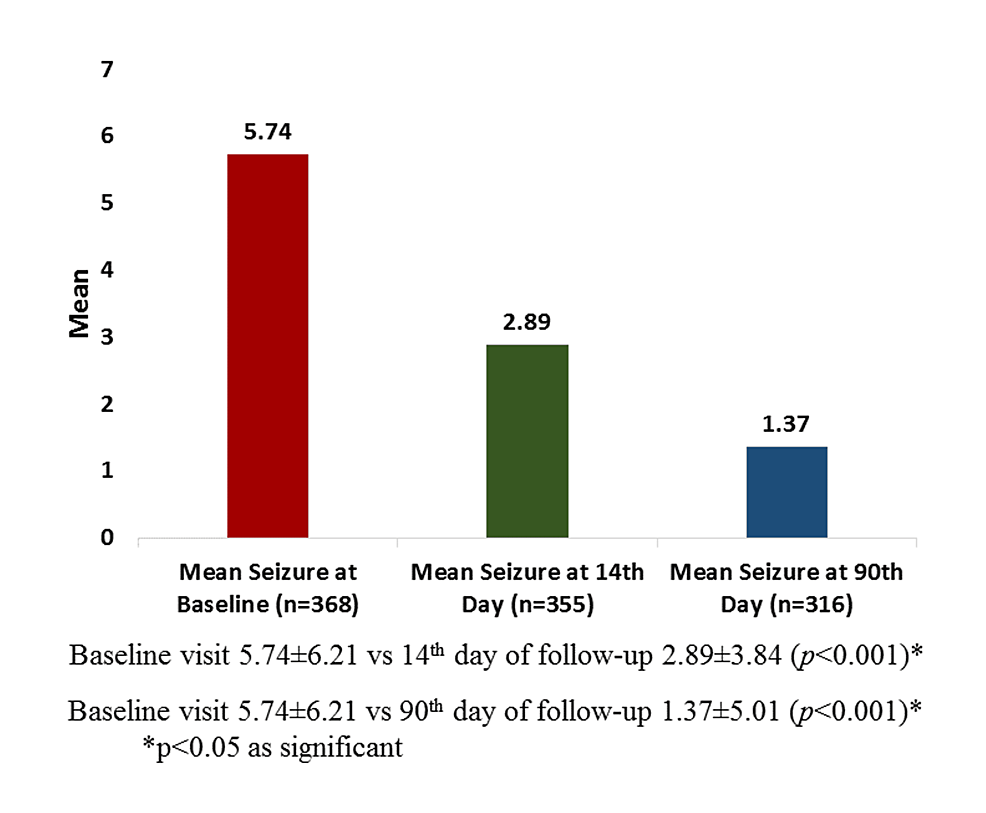

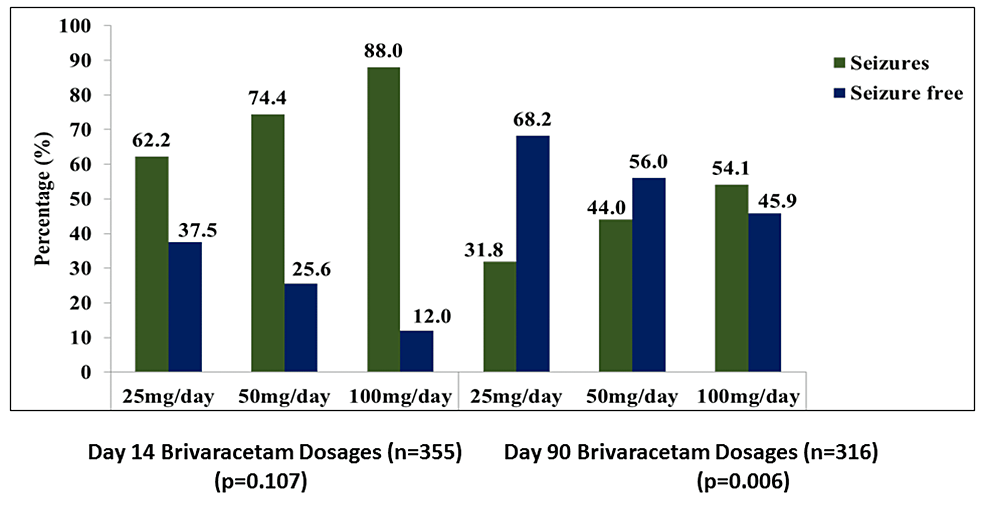

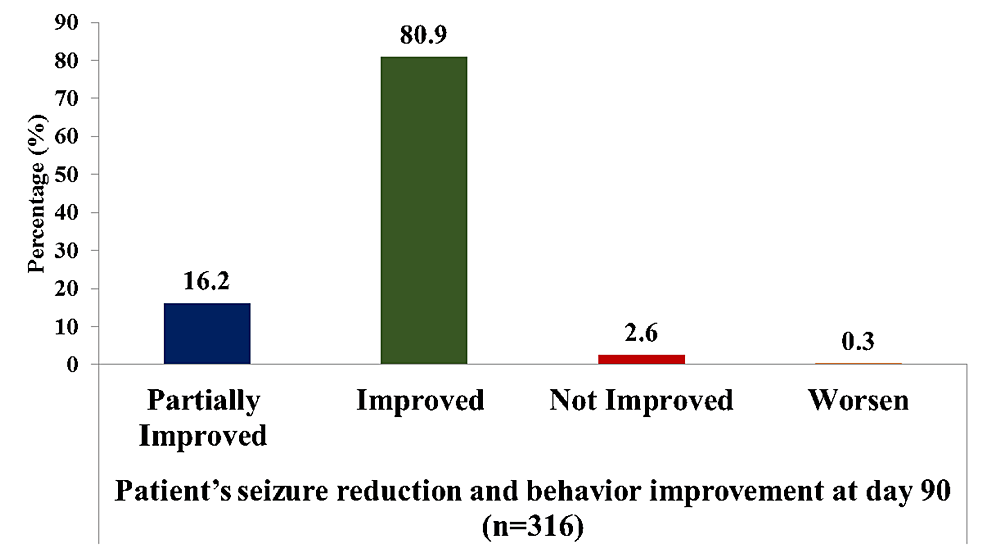

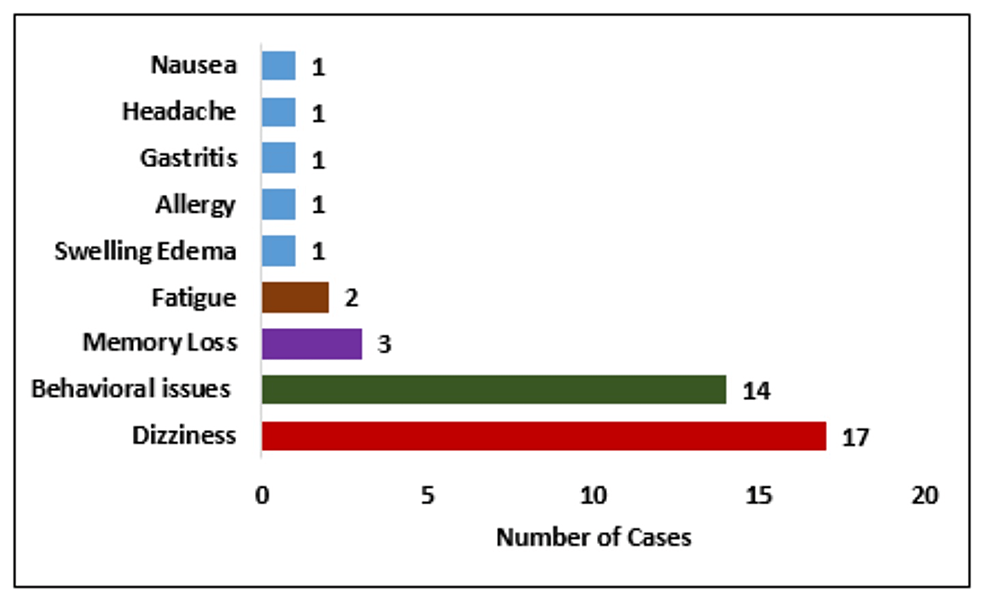

Results: Across four clinical sites, 543 individuals participated, with a mean age of 32.9 years. The most prescribed dosages were 50 mg BD, followed by 100 mg BD. Notably, brivaracetam combined with divalproex sodium was the most prevalent treatment, followed by brivaracetam with levetiracetam. At both the 14th and 90th day assessments, a significant reduction in seizure frequency was observed, with 63.1% of individuals showing a favourable response by day 90. Treatment-naive individuals exhibited higher rates of seizure freedom and response compared with treatment-resistant individuals.

Conclusions: The study demonstrates the effectiveness of brivaracetam combination therapy in epilepsy management, with notable reductions in seizure frequency and favourable clinical responses observed, particularly in treatment-naive individuals.